History books are replete with accounts of the American colonists’ fight for independence. However, few literary offerings are available depicting the participation of America’s first allies – the Oneida – in the Revolution. Oneidas stood with the colonists as stalwart partners during their fight for freedom.

Testimonies do, however, exist about the Oneidas’ involvement in the war, including those taken from the Draper Manuscripts, chronicling interviews with Oneidas from Oct. 30 to Nov. 2, 1877, sharing their knowledge of war. The following are a few of those Oneidas recalling their family’s experiences during the Revolution.

Neddy King, who was born in 1821, said his grandfather was in the Battle of Oriskany Aug. 6, 1777.

Henry Powless, either 79 or 85, stated that Hon Yerry Doxtator and other Oneidas were at the Battle of Oriskany and also helped to fend off the British and their Indian allies, who were attempting to destroy Fort Stanwix.

Cornelius Doxtator, 55, offered a list of Oneidas, who were commissioned by Congress in 1779, comparing his spelling of the Oneida names (and offering translations) with the ones designated by Congress:

Hon Yerry Doxtator, designated by Congress as Hansjurie Te-wah-on-grah-kon. Cornelius wrote the name Th-haw-en-ka-rag-wen, meaning, He who takes up the Snow Shoe.

An Oneida captain listed by Congress as Te-wag-tah-kot-te, which Cornelius stated was Te-wash-ko-te, meaning, The Standing Bridge.

Another captain recorded by Congress was John O-laa-wig-ton; Cornelius wrote it O-la-a-wis-ton-e, The Silver Smith.

Congress wrote Tha-o-sa-gwat, His Lips Followed Him; Cornelius listed him as Han Yost Tha-ho-swa-gwat.

Further accounts of the Oneidas in the Revolution were provided in the manuscript by descendents, including the story of Paul Powless or Ta-ha-swau-ga-lo-lus, Saw Mill, as told by his son, Henry:

Paul was a chief and was present at the siege of Fort Stanwix. He acted as an express (messenger) and spy for the colonists. Additional Oneidas were also at the fort – some inside, others outside as spies and pickets (lookouts).

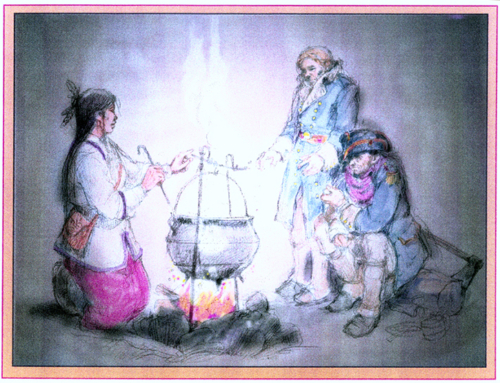

Alone in the woods miles from the fort, Paul came upon the approaching enemy, who also discovered him. (Joseph) Brant – a Mohawk, siding with the British – called to him to cease his retreat and pledged no harm would befall him. Paul raised his weapon and asked Brant to come and speak to him alone. Brant agreed. Paul kept his weapon on Brant with his finger on the trigger and told Brant to speak his mind.

The following is directly taken from Paul’s son’s recollection of his father’s experience with Brant:

“…. [he] bade Brant deliver whatever message he had to offer. Brant insinuatingly offered him a large reward, and a plenty as long as he should live, if he would only join the King’s side, and induce other Oneidas to do so, and help the British to take Fort Stanwix. Powless firmly rejected any such blandishments, saying he and his brother Oneidas had joined their fortunes with those of the Americans and should share with them whatever good or ill might come. Brant portrayed the great and resistless power of the King, and profess[ed] to deplore the ruin of the Oneidas if they should foolishly and recklessly persist in their determination. Powless replied that he and the Oneidas would persevere, if need be, till all were annihilated; and that was all he had to say, when each retired his own way.”

After the above interchange, Paul met up with his fellow Oneida pickets, all of whom had to fight their way into the fort “in some measure,” as Brant’s retinue was already laying siege. The British started to dig under the fort, preparing to blow it up. The Oneidas, according to Paul “…used to say, if they had not been there to aid in its defense, the fort might not have been saved.” Paul later in the night snuck out of the fort and found his way alone to Schenectady, seeking aid for the beleaguered fort.