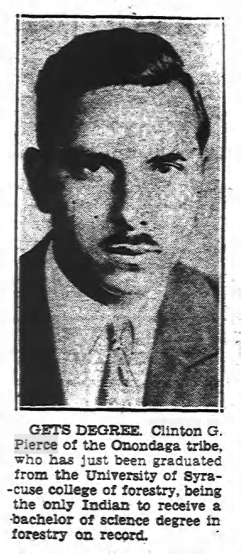

During the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” created the Indian Emergency Conservation Work (IECW) program, which later morphed into the Civilian Conservation Corps–Indian Division (CCC-ID). And Clinton Pierce (Turtle Clan, 1909-1977), the first American Indian to graduate from the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse University, was the group foreman for the CCC-ID projects on the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) reservations.

The programs that existed between 1933 and 1942 were designed to provide jobs for American Indians across the country, working on roads, bridges, clinics, shelters and additional public works near their reservations. Men were also offered training as carpenters, truck drivers, radio operators, mechanics, surveyors and technicians.

According to the book The Iroquois and the New Deal by Laurence M. Hauptman: “Because of Pierce’s excellent work in carefully establishing the IECW program in New York, the Indian Service promoted him by transferring him to the Klamath Reservation [Oregon] in the Pacific Northwest in December 1935. But the New York agency carried out Pierce’s suggestions.”

And his suggestions were many, but first he provided a report describing the different reservations, their topography and the conservationist concerns and problems the people were encountering. Hauptman outlined Clinton’s proposed projects, which included regulating, protecting and developing Indian forest lands; clearing brush to reduce fires; building tract trails to facilitate removal of various wood; fencing, posting and marking reservation boundaries to prevent “white encroachment;” establishing fire lanes to avert the spread of fires; and starting flood control and soil erosion prevention projects by means of straightening streams, cleaning channels of logjams and debris, and creating drainage ditches. His programs were implemented in 1935.

But, perhaps most notably, Hauptman quoted Clinton, who was one of the few “foresters of Indian descent in the country,” as saying that Indians held “strong feelings of independence” and had a “strong tendency to dictate rather than to be dictated to.” Clinton also warned that any conservation effort must be first cleared through the tribal councils. That advice was taken to heart by federal officials and administrators, who attempted to contact tribal leaders on each reservation.

A 1932 newspaper caption erroneously identified Clinton Pierce as Onondaga. At the time many Oneidas lived on Onondaga lands, and some still do today.

The program, while deemed successful, also encountered roadblocks. Clinton had to borrow equipment – tools, cars, trucks, tractors and more – from New York State and the county road engineers when available. Additionally, Hauptman points out the double standards that applied on the reservations. He quotes Clinton as saying, “The local relief agencies pay a larger wage scale and they pay at the end of each week. Under our regulations, it requires two times as much work to earn the same pay and necessitates waiting several weeks for their pay.”

Beryl (née Pierce) Smith (Turtle Clan), Clinton’s niece, said Clinton remained out West for the rest of his life, working for the forestry service. But she remembers him from her childhood when he would come home from college and bring friends from all over the world with him.

“One time he would bring home an African and next time a German,” said Beryl. “I became accustomed to all races of people.”

Great-niece Wava Carpenter (Turtle Clan), who passed in 2011, remembered Clinton “as a very handsome man. He loved all the kids and my mother (Sadie Pierce Thomas) had 13 of us. He married and had one daughter. Clinton would come back every five years or so from his home in Montana to visit his father and mother (Lavina George Pierce).”

While at SU, Clinton played lacrosse, making the All Team Participation List for 1930, 1931 and 1932. In 1932, the year he graduated, he was named as an honorable mention as a wing attack on the All American Syracuse Lacrosse team.

Clinton Pierce (who died at 68) broke barriers, becoming the first Indian to graduate from the forestry school at SU and being hired as one of the few American Indians foresters in the country, excelling in each endeavor. His name continues to resonate within his huge extended family, where he is remembered with pride.

This story originally published in The Oneida, Issue 7, Vol. 11, October/November 2009