By Kandice Watson (Wolf Clan), Documentarian

The Oneida Indian Nation has always been known as “The People of the Standing Stone”, “The Granite People”, among others. Of course, it is impossible for us to know the exact origins of the “standing stone” name, but it has defined us as a people since time immemorial. There were many stones associated with the Oneida Indian Nation and it is doubtful that any one single stone was the Oneida Stone.

Oneida legend states that the stone would follow the people wherever they went and would always end up on the outskirts of the village after they moved. Other legends say that the stone would lead the people to their new village, which to me, seems to make a bit more sense.

When the people lived in a certain area for some time, the soil could become less fertile and unable to grow crops when compared to the beginning of their time there; or perhaps the game had become scarce and the men were required to travel further and further distances to acquire meat. For whatever reason, the people would have to move their village roughly every 10 – 15 years. To ensure a smooth transition, some men would go out and scout new areas to relocate. They would have to find an area that met all of the requirements needed for a successful village, which included a fresh, clean water source, rich, fertile soil, ample game for hunting, and plenty of fish available as well. After securing all of these items, the men would look around to find a substantial stone that could be used for ceremonies or as a gathering space. Once all of these requirements were met, they would begin to prepare the land for settlement. Oftentimes, they might find a very good region with all the necessities so they could re-use that spot many times, with decades in between encampments. Perhaps they remembered stories of their grandparents’ villages and re-occupied them later with their own children.

The larger villages were known as the principal villages, with many smaller villages in the surrounding vicinity. The smaller villages may had their own stone that could be moved from place to place, but the larger stones in the principal villages were too large to move. Oftentimes, smaller stones were painted red and placed up in the trees to signify Oneida territorial boundaries. In 1746, when asked to display their National symbol, the Oneidas placed a red-painted rock in a tree (O’Callaghan 1849-51, 4:432). This identification was repeated several times throughout the early 18th century by the Oneidas, so there is no doubt they identified with a stone.

In 1796, south of Kanonwalohale (present day Oneida Castle), travelers Jeremy Belknap and Jedidiah Morse encountered an Oneida stone in front of the home of an old man named Silversmith, aged about 80. In his book, Rebellious Younger Brother, David Norton explains that this man was Alawistonis, who had been named Leader of the Pagan Party and Keeper of the Stone after the Revolutionary War. He was a warrior from the Wolf Clan and was the nephew of Agwlongdongwas (Good Peter) but did not share Agwlongdongwas’s affection for Christianity. He kept his home at Old Oneida, which was situated on Primes Hill in Munnsville, and did not move to Kanonwalohale along with his uncle after the religious upheaval that occurred there.

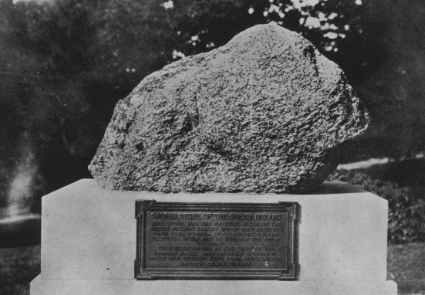

This specific stone is the one that was moved to the Forest Hills Cemetery in Utica, NY in 1846 (The Sabbath Recorder, 12/6/ 1849). It sat on the ground there for many years before being placed upon a granite pedestal where it remained undisturbed until May 1974 when it was returned to the Nation’s thirty-two acre reservation. The stone was placed in front of Delia Waterman’s white house on the reservation and tobacco was burned in recognition of its return (Syracuse Post Standard, 5/24/1974). The people held a feast and a plate of food was prepared for the stone and placed atop it. The stone was later moved to its current location, next to the Oneida Indian Nation Council House near the end of Territory Road where it will remain.

There are other stones that some claim to be the Oneida Stone. There is a large boulder at the Nichols Pond site that Henry Schoolcraft asserted was the Oneida stone. He drew several pictures of this stone, which were distributed widely, leading to much confusion. This may have been the Oneida Stone at one point, but it is too large to follow anyone anywhere.

Another stone that has gained notoriety, which is often confused with the Oneida Stone, is Skenandoa’s Boulder. This stone sits near the location of where his house stood during the Revolutionary War. He hosted many dignitaries as well as state and federal officials in his home, including Timothy Pickering, the Indian agent who prepared the Schedule of Losses in 1794.

A curious stone located in Huntingdon, PA must also be mentioned when discussing the Oneida Stone. Prior to and during the Revolutionary War, the Oneidas were known as “The Keepers of the Southern Door” and often had a village in the southern region. One village was known as Oquaga, which is located near present day Harpursville, NY and another near Juniata, PA which was later renamed Huntingdon. Juniata history tells of a stone 14’ tall, 6” square on each side that they claim is the Oneida Stone, and it sat in the middle of the village. Conrad Weiser, an Indian trader, recorded a reference to the standing stone in a journal of his travels through the area in 1748. His account relays that the Tuscarora Nation stole this stone and secreted it off into the woods where the Oneidas later found it. Over time, the stone was lost and a replica was situated in its place in around 1896, which still stands today. This stone is the only one that I would truly call a Standing Stone, in the sense that it is more of an obelisk, which is what we normally think of when discussing a standing stone.

The Oneida Stone will forever be thought of fondly by its people and we can be assured that it now rests where it will remain forever, next to our Council House on original Oneida homelands.