Annual Dig Helps Oneida, American Indian Youth Connect

To the untrained eye the items drying off on towels labeled site one and site two inside the Oneida Indian Nation Cookhouse on a recent Friday morning looked like mere rocks.

To the trained eye, and with the guidance of Jesse Bergevin, historic resource specialist with the Oneida Indian Nation, the pieces transformed from rock to everyday tools. And while whole pieces were not found during a dig on a site that dates back between the years 1450-1470, the shards and pieces of chert, a common material with properties similar to glass that is easy to shape and chip, are just as important. When taken in totality these pieces become the evidence needed to establish village locations significant to the Oneida Indian Nation.

“Some of these rocks have a butter-knife edge to it, that’s what we were looking for,” explained 15-year-old Jaden Confer (Turtle Clan) who worked on the site. Jaden said the work was tedious and hot, but the prominence of this site, located off a busy road in Madison County, was not lost on him.

“It was pretty cool to see the different kind of rocks and evidence of different times (such as objects used by occupants of the house on site). It was really cool finding the arrowhead,” Jaden continued.

Jaden is a first-year participant in the Oneida Indian Nation’s Youth Work Learn program. For more than 20 years YWL has been offering Oneida and American Indian youth real job experiences during a six-week summer run. Jaden, who was joined by returning workers Alaina Beane and Dylan Curtis, both 15, helped excavate two separate test units. They were looking for stone tools, ceramic pieces, palisade lines and evidence of longhouses, all at a site located on Oneida Indian Nation homelands that is dated prior to European contact.

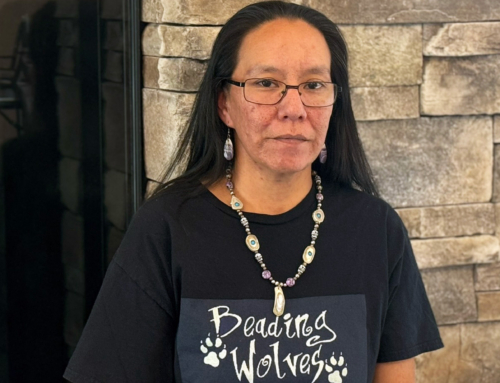

Kandice Watson (Wolf Clan), director of education and cultural outreach for the Oneida Indian Nation, underscored the significance of finding such objects, even with the smallest of items.

“We always say this is Oneida country and this is Oneida homeland but when the kids actually know for sure this is where our people lived, that they can actually stand on the same ground their ancestors stood on, dig in that same dirt, I think it becomes more real as an Indian person when you know your ancestors were in this spot,” Kandice said. “It’s a little different once you can actually dig this out of the ground and know — to have (this) proof – that they were here.”

As Oneida moved to different areas over time, Kandice further emphasized the significance of this dig, telling participants, “you are very fortunate to be able to do this and that the Nation has been able to acquire these lands to give you the opportunity. It really makes a good connection with our homelands and the earth, just so we know exactly where we belong.”

“What we did find was a mix (of objects)… like a portion of a projectile point (arrowhead) and pieces of pottery, that were related to the Oneida occupation of the area,” explained Jesse. “Later…there was a house built on the site. So we did find evidence of activities and materials related to the house and later land use from the mid-1800s through modern time. For example the pottery, some of the ceramics, pieces of plates and such and all sorts of nails – square nails all the way through to round nails.”

The Oneida Indian Nation Youth Work Learn program allows participants to earn money while learning the basics of holding a job, time management and career preparedness. The program is open to Oneida Indian Nation Members and other American Indians. Participants must meet educational requirements in order to qualify.