From the March 2005 edition of The Oneida: Issue 2, Volume 8.

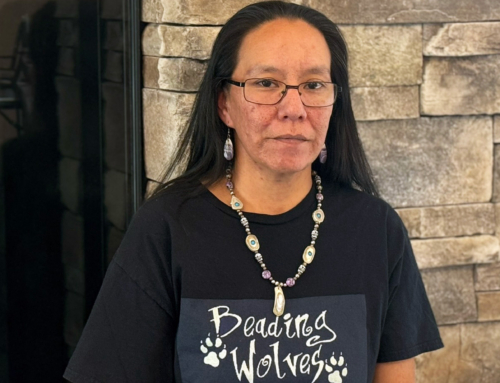

In a quiet acquisition last year, the Nation purchased a collection of Haudenosaunee items that included an Oneida woman’s regalia, circa 1870. The purchase of the raiment in and of itself is momentous, as the regalia is complete and in wondrous condition. The regalia, however, took on a new life, becoming a catalyst that eventually led to a renowned artist in England gifting a painting featuring the outfit to the Nation.

The story begins with antique dealer Frank Bergevin, from whom the regalia, and the rest of the collection, was purchased. Over the years, the Nation has purchased several Haudenosaunee items from Frank, but it was his acquisition of the regalia that began a fortuitous chain of events.

“I’ll never find anything as important as the regalia again,” said Frank. “It is the most important thing I have ever found in my life. It was sheer luck that it was Oneida, and I wanted it to go back to them. I also wanted it to come to life somehow; otherwise it was just a dress. The Oneida have been good to me, and I wanted to do something special for them.”

Thus, the idea for the painting began to take form. At first Frank contemplated having someone don the outfit for a photograph. He quickly dismissed the idea when he remembered a painting of a Haudenosaunee woman he had been given by a British friend. This particular friend of Frank’s, Mark Sykes, is also a collector of Iroquoian items, as well as being one of Frank’s suppliers. And Mark, in turn, is friends with Richard Hook, an English artist of repute, who is noted for his illustrations of soldiers from different periods and of American Indians.

Mark acted as the liaison, contacting the artist with Frank’s request to feature the regalia in a painting. Richard accepted Frank’s commission. But before brush could be put to canvas, certain particulars needed to be worked through, including a model for the woman wearing the regalia.

Frank asked Tony Wonderley, Nation historian, for a copy of a photograph of an Oneida woman. The photo chosen was of Anna Johnson Sconondoah (Turtle Clan) taken in 1905. A photo of an Oneida-made basket, along with its specifications, and photos of the regalia were also sent to the painter.

When the painting, “Portrait of an Onyota a ka Woman,” was completed, Richard refused Frank’s remuneration for his work. Richard is an avid collector of American Indian articles and a researcher and this passion has become his avocation.

“I didn’t charge for it because I did it for the love of it,” said Richard, via telephone from his home in Sussex. “My interest in American Indians has given me a lot of pleasure, and I wanted to give something back.”

Regalia Part of a Greater Collection

As is true with many tales in life, there is a story behind the story. The regalia is part of a collection of Haudenosaunee items the Nation purchased. The remaining objects are largely beaded works, mostly found in England.

But how, one might wonder, did these Iroquois items end up overseas? According to Mark and Richard, there are several explanations and each helped to fuel the economy of Oneidas who were creating the beautifully crafted objects.

According to Mark, during the 19th century’s Victorian era, Niagara Falls was a romantic American destination for the British and one where Haudenosaunee items were readily available for sale.

“People acquired items as curio pieces,” said Mark. “People would say the items were made by an American Indian. It benefited the Indians.”

But the English didn’t necessarily have to go to the States to purchase these objects; traveling Wild West Shows and circuses sold the pieces in Britain. And, the Victorians held large exhibitions during this era, and American Indian beaded work was included.

“Iroquois beadwork by the crate-load was brought over and was very popular,” said Richard. “There are photos of Victorian women beautifully dressed, carrying Iroquois purses and they didn’t know what they were.”

Interest in Haudenosaunee items didn’t wane with the ending of the Victorian era, however. During World War II, American GIs in England brought over beaded pieces and gave them to girlfriends.

“Beaded bags stood the test of time, unlike silk stockings,” said Mark.

After the war, in the 1950s and ‘60s, beaded work remained a fascination in England and was still affordable and available at local markets. But by the 1970s and ‘80s, fewer pieces were accessible and prices began to escalate.

Fueling of a Passion

The two Englishman share a love of American Indian culture and artwork that began in childhood. And each began their collection with a piece of Haudenosaunee work. For Richard Hook, the allure began when he was a boy and purchased a set of beaded baby moccasins, which he still owns. Mark’s initial purchase was a beaded purse, which is among a collection that he sold.

“When I visited the Nation, the first piece Tony Wonderley showed me was the first piece I bought when I was 13 years old,” said Mark from his home in Leeds, where he works for the local government in dispute resolution. “That piece was the catalyst of my interest for the material. It was ironic that I should hold my first piece that I collected at the Oneida Indian Nation. I never felt it belonged to me anyway. I would never have sold it if it weren’t going back to the people who made it.”

This sentiment of Mark’s is the overriding reason for his continued quest for Haudenosaunee pieces. Mark said he can no longer afford to keep the beaded works, so when he does find items he sells them for cost to buyers who will bring them back to those who made the pieces, such as the Oneida.

Safeguarding pieces that are in bad repair has become another of Mark’s interests. He said he purposely buys beaded works that are in a distressed state – those pieces that had more use or neglect – and restores them, strengthening the threads of the material without changing the character of the piece.

Again, Mark charges no fee for his restoration work, stating, “I feel like I’m giving something back and safeguarding the pieces for the future, repatriating the pieces back to the people who made them. These artisans were very underestimated. Each piece has its own story to tell.”

For Richard’s part, he has collected a library focusing on American Indians and has acquired a collection of artifacts – many purchased during his trips to the States. In the past, American Indian items were readily available at flea markets in England, but no longer, as eBay is the current venue, said Richard.

“I never tire of American Indian articles, particularly as an artist,” said Richard. “I can draw it and never tire of it. As an artist I find American Indians visually stimulating.”

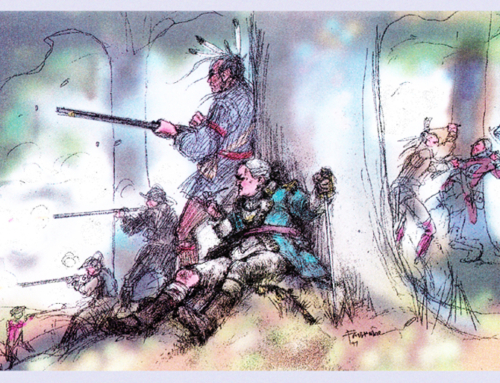

As much as he admits to loving to paint images of American Indians, he restricts the times he allows himself to indulge his passions. Richard earns his living illustrating books, including, “The Confederate Army 1861-65,” “Samurai Commanders” and “Spanish Guerillas in the Peninsular War 1808-14.”

Although these books represent Richard’s weekday world, it is his paintings of American Indians that represent the work of his free time – free time he covetously guards against overuse.

“My fun time is painting American Indians, so I don’t want to take on commissions painting them because it will ruin my hobby,” said Richard. “I don’t want to destroy my hobby. I look forward to it.”

That is why it was so unusual for Richard to have accepted the commission to create a painting around the regalia. But it is his true appreciation for the culture of the American Indians that led to his gift.

Richard explains his passion this way:

“It’s the grass-is-greener syndrome. If I’m talking to friends in the States, they’re fascinated that I live near the site of the Battle of Hastings (referring to the 1066 Norman Conquest led by William the Conqueror, who took the English throne). I don’t even look at it. But when I came to the States, people told me I’d be disappointed. I adored it; it exceeded my expectations. I traveled in Montana and Canada, all around the Indian areas. This history is what holds my interest.”

The Collection

In August, the remainder of the collection, which included the regalia, will be delivered to the Nation. Many of the items came from England and were Mark’s finds. Among the items in the newest assemblage are 70 beaded purses; 60 additional beaded items, including pincushions, needle cases and watch pockets; 20 pairs of moccasins; 20 baskets; 15 wooden pieces, including a cradle board from the 1870s; and several cornhusk pieces and items of clothing.

These items add to the Nation’s already considerable existing collection that began with the purchases of 170 beaded works and burgeoned with the next acquisition of 328 items that included moccasins, purses, pincushions, hats and whimsies – fanciful souvenir objects.

“These collections mark the Nation as owners of one of the world’s premier collections of this material,” said Tony, who facilitated the purchase of the items.

The beadwork was adapted to appeal to tourists, but the methods employed by the Haudenosaunee to create the built-up decorative surface that is indicative of the beaded art form are ancient. The beadwork often was emblazoned with the location where the beadwork was being sold. It was a survival art form begun at a time when the Haudenosaunee were impoverished and struggling to continue under conditions of devastating cultural loss, said Tony. The initial purchasers of these items bought them for a pittance compared with their current market value, which has increased with time.

“The Oneida and the other Iroquois used their talents for beadwork and other artwork as a means to ensure their continued survival,” said Keller George, Wolf Clan Council Member. “We took advantage of the tourist market and adapted our work to please outsiders. At a time when few opportunities were available to Indian people, we saw a market and geared our designs to appeal to that market. It was a survival technique and now with the acquisition of some of the work made during that period we have tangibles that can help us tell another part of our story.

“It is interesting to me to think that people far removed from the Nation, like Richard Hook, should take such an interest in Indian people and their culture and heritage. The painting he so graciously donated to the Nation will laud him in the stories of our people to the seventh generation and beyond.”

This article was written by Susan Hébert George and originally appeared in the March 2005 version of The Oneida: Issue 2, Volume 8.