Little is known about the woman who symbolizes the loyalty and dedication the Oneida Indian Nation displayed as America’s First Allies during the Revolutionary War

By Kandice Watson (Wolf Clan)

Documentarian, Oneida Indian Nation

The Oneida Indian Nation has always been very proud to be known as America’s first ally, and we have known for years of the various accomplishments and contributions made by our ancestors in the effort for America’s independence.

Polly Cooper is just one of our ancestors that we remember fondly when recounting her efforts as a cook during the Revolutionary War. The winter of 1777-1778 was especially brutal, and Gen. George Washington’s army was in dire straits while hunkering down in Valley Forge.

Washington was in need of knowledgeable Indian scouts and in the fall of 1777, he had requested the Marquis de Lafayette recruit some Oneida warriors for this important work. He had suggested Lafayette secure around 200 warriors; a number that alarmed the principal Oneida village of Kanonwalohale, which could barely afford to send 50 warriors. The times were tough for the Oneidas in the winter of 1777-1778, and they could ill afford to send anyone anywhere. However, incidents that occurred that fall prompted the Oneidas to choose to side with the rebels.

The village of Oriska had just been destroyed in September of 1777 by Joseph Brant and British loyalists, and the Oneidas were finding it very hard to remain neutral. When Washington sent his request for warriors, the destruction of Oriska was still very clear in everyone’s memory, and Lafayette was able to recruit 47 warriors to join him on the long, cold trek south to join General Washington.

Among those that accompanied Lafayette to Valley Forge were: Han Yerry (Tewahongarahkon), Sachem Thomas Sinavis, Hon Yost Thaosagwat (Han Yerry’s older brother), Jacob Reed (Aksiaktatye, Oneida interpreter), Henry Cornelius (Suggoyonetau), Blatcop Tonyentagoyon, Deacon Thomas (Samuel Kirkland’s assistant), Daniel Teouneslees (Skenandoah’s son) and a young woman named Polly Cooper.

The group departed Kanonwalohale on April 25, 1778 in a cold April snow. They arrived in Valley Forge on May 15, 1778, and upon their arrival, one of the American soldiers noted in his journal: “A few days ago, 40 Indians, of the Oneida [Indian] nation, arrived at our camp, they are to join Col. Morgan’s corps, and to scout near the lines; to check the unlawful commerce, too much carried on at present, between the country and the city.” (Extract of a letter from Camp, 13 May 1778, New York Journal, 1 June 1778.)

The soldiers, however, made no mention of Polly Cooper being with the men. Perhaps they simply did not notice her among them.

Many accounts of this trip categorized it as more of a relief mission, with the Oneidas bringing corn to assist the starving soldiers. However, in reality, the corn was merely an additional bonus. The warriors went to Valley Forge because General Washington had requested their assistance.

The Oneidas were said to have brought anywhere between 60 and 600 bushels of corn on the trip. We know the Oneidas had access to some horses at the time, and word is they brought a few horses with them. As a mathematician, I ran the calculations and determined that one horse could have carried approximately 1/5 of its body weight – roughly 200 lbs. – which is about 5 bushels of dried corn by weight. If the party had 5 horses, they could have carried around 25-30 bushels, maximum. Each warrior could also carry one bushel, so by these figures, they brought at most 60 -70 bushels of corn with them.

When they arrived at the winter camp, the story often was told that the soldiers were so hungry, they attempted to eat the corn raw, but were stopped by Polly, who instructed them on how to cook the corn. The hulls on white Indian corn are much harder and take much longer to cook than regular sweet corn. In addition, it requires extensive rinsing and cleaning before preparation.

More than likely, she prepared many different meals for the men, including corn soup, corn bread and mush, sometimes adding strawberries or nuts to the mix, enhancing the flavor and nutritional value of the corn. The delicious meals Polly prepared would have immediately boosted the morale of the men, and was a welcome addition to the few rations they were receiving.

While Polly prepared and taught the men how to cook, the Oneida warriors that accompanied her were on their way to Barren Hill to experience their first real attempt at combat. The Oneidas followed Lafayette’s lead, but soon found themselves in serious trouble as the British began to approach. There was a small battle at Barren Hill, and one Oneida, Thomas Sinavis, lost his life. Sinavis was of the Bear Clan and was a hereditary sachem. His sister, Wale’ was a Bear Clan mother, and she was devastated by the loss of her brother. Thomas is buried in the Presbyterian St. Peter’s Church cemetery in Barren Hill.

Two Oneidas were also captured as prisoners that day and returned to Philadelphia where they were stripped of everything except their breechcloths. One of these Oneidas was Skayowi:yoh (Beautiful Sky).

After the death of Sinavis, General Washington changed his mind about the Oneida warriors fighting in combat and desired for them to return home. The price they were to pay was too high, and they were needed at home to protect their families more than they were needed in Pennsylvania.

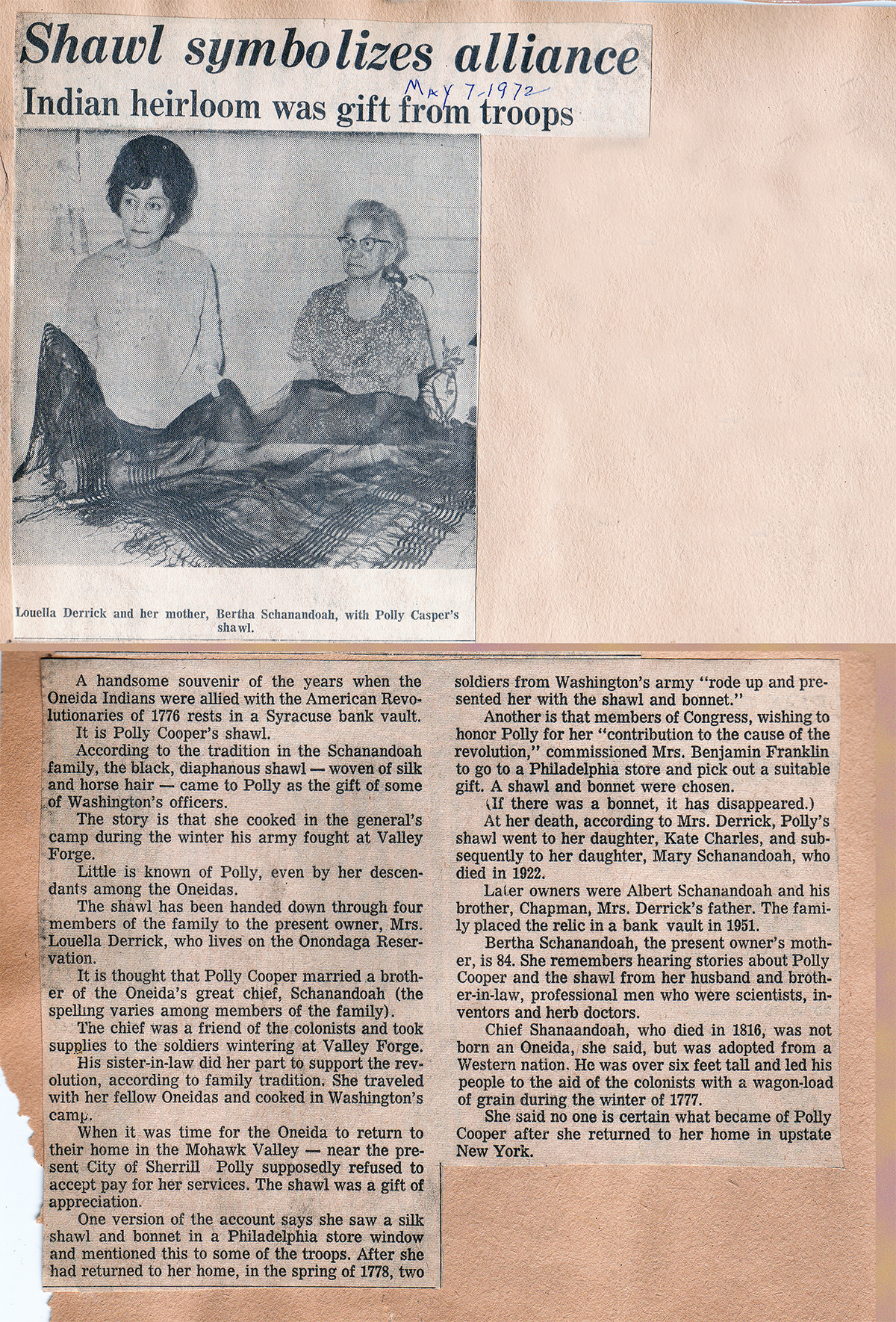

The Polly Cooper Shawl.

In mid-June, 34 Oneidas returned home to Kanonwalohale, which more than likely included Polly Cooper. After showing the men how to cook the corn for a few weeks, she was offered payment for her services, which she refused. Oral tradition says that she and some of the other wives of the soldiers were window shopping in Philadelphia one afternoon when she admired a shawl and bonnet in a store front window. The wives made note of it and later asked their husbands to purchase the items for her. Her descendants tell of two soldiers appearing at her door a few weeks after they returned home with a package containing the shawl and bonnet. The remaining Oneida warriors returned home in July.

Throughout the years, the bonnet was lost, but the shawl remains today in the possession of Polly’s descendants. The material the shawl is made from is very unique and cannot be accurately identified. Some say it is horse hair, others claim it is silk, though neither can be precisely determined. Nonetheless, it is a priceless item for the Oneida Indian Nation, and solidifies our recollections of Polly.

Some scholars question this story, as there are no recorded papers showing these items being purchased for Polly and no mention is made of her in any soldier’s journals at the time, which is peculiar. Some feel we may have her confused with a different Polly Cooper, who is recorded as serving as a cook in the War of 1812. She enlisted in 1813 at the age of 31, so this cannot be the same Polly Cooper from the Revolutionary War timeframe, but could be a possible namesake or descendant of Polly. It was customary for names to be re-used when someone passed away and this may have been the case with Polly.

Newspaper article from May 7, 1972.