Over two hundred years ago, near the site of the present-day Oriskany Battlefield Historic Site, there stood a thriving Oneida village called Oriska. In that village, Oneidas cared for their children and attended to their homes. They tended their crops, and stored the excess for the harsh winter months. They, like their colonial neighbors, lived their lives. Everything would change in a short time, however, as war came to the region and took its toll upon Oneida and colonist alike.

As with the other villages that comprised the Oneida Indian Nation of over two centuries ago, the Oneida people lived under the fundamental principles of democracy. It was that belief in freedom that brought the Oneidas to the aid of the colonists during the Revolutionary War, marking the Oneidas as the United States’ first allies.

But it was not an easy decision. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, comprised of the Oneida, Tuscarora, Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga and Seneca, could not agree at the onset of the American Revolution if they should war against the colonies. The Oneidas were opposed to any such hostility and because of their dissent unanimity among the nations could not be reached. Thus, the proposal to wage war as a confederacy against the colonists was defeated.

But just as the Oneidas had ties to their colonial neighbors, others within the confederacy had their own allegiances. It was therefore determined by the confederacy that each individual nation could decide for itself whether or not to engage in the war and on which side. The Oneidas chose the colonists.

“I often wish that I could look back through time and hear the words of my ancestors as they sat around the council fires deliberating on whether to join the colonists in battle,” said Keller George, Wolf Clan Member of the Oneida Indian Nation’s Council. “I wish I could listen to the wisdom of their arguments to join the United States and become its first allies.

“Our people have always made decisions based upon how it will affect the seventh generation to come. I know that the decision my ancestors made over 200 years ago, around those ancient fires, was made with the consideration for the faces yet unborn. I represent one of those faces and I thank my ancestors for their wisdom in choosing to aid this great country at its birth.”

Once the decision was made, the Oneidas, and their adopted brothers the Tuscaroras, entered the fray, fighting side by side in many crucial battles of the war, including the Battle of Oriskany on Aug. 6, 1777.

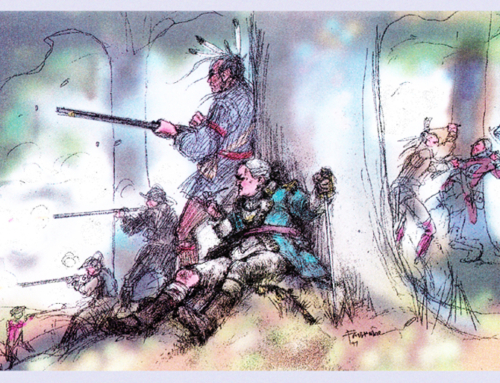

On that hot summer day, about 60 Oneidas along with the Tryon County Militia under the command of Gen. Nicholas Herkimer were ambushed at Oriskany by British troops and their Haudenosaunee allies. Herkimer and his contingent had been on their way to help the forces at Fort Stanwix that were under siege by the British when attacked.

The battle that ensued at Oriskany would prove bloody. Among the wounded was an Oneida man, Han Yerry, who was shot in the wrist. Han Yerry remained on the battlefield, however, despite his injury. With the help of his wife, Tyonajanegen, who loaded his gun, he continued to fight. Tyonajanegen did more than aid her husband however, she also brandished her own pistols.

Newspaper reports from the period detail Han Yerry and Tyonajanegen’s valor. For six hours, the duration of the battle, Tyonajanegen fought side by side next to her husband. Tyonajanegen also notified the other colonists of the great bloodshed that had resulted from the British ambush at Oriskany.

Perhaps as many 500 people died in the opening volley of the battle, with Gen. Herkimer sustaining a wound that would prove fatal. However, the battle ultimately contributed to a military victory for the colonists.

The battle was decisive to the outcome of the war because the Oneidas and the militia under Herkimer’s command were able to thwart the advance of a British expeditionary force marching from the Great Lakes under Gen. St. Leger, who was attempting to move east and join Gen. Burgoyne and his forces, who were marching south from Canada. If the two forces had united, they could have successfully divided the colonies in half.

The Oneidas and the colonists successfully prevented the British forces from joining, a pivotal event that would contribute to Burgoyne’s loss at the Battle of Saratoga. Few names are readily recalled from that fatal day at Oriskany, aside from that of Herkimer, and for the Oneida people, Han Yerry. But the names of other Oneidas live on including, Henry Cornelius, Blatcop and Honyoust.

The Oneidas involvement in the colonists’ cause for freedom was not limited to the Battle of Oriskany. Oneida warriors fought at additional key battles of the American Revolution, including the Battle of Saratoga in September, 1777. Oneida scouts were also recruited to provide much-needed reconnaissance during the war.

The Continental Congress acknowledged the Oneidas’ contribution to the War of Independence in December 1777:

“We have experienced your love, strong as the oak, and your fidelity, unchangeable as truth. You have kept fast to the ancient covenant chain, and preserved it free from rust and decay, and bright as silver. Like brave men, for glory you despised danger: you stood forth, in the cause of your friends, and ventured your lives in our battles. While the sun and moon continue to give light to the world, we shall love and respect you. As our trusty friends, we shall protect you; and shall at all times consider your welfare as our own.”

The Oneidas also played a role in the war effort during the winter of 1777-78. George Washington’s troops were freezing and starving at their encampment at Valley Forge. The soldiers were not prepared for the extreme cold and some had no shoes, boots or warm clothing. The troops were in dire need and morale was understandably low.

Help came to Washington’s soldiers when a group of several Oneidas, assembled by Chief Shenendoah, walked several hundred miles carrying hundreds of bushels of corn. When they arrived, the hungry soldiers tried to eat the corn raw. The Oneidas knew that if the corn was eaten uncooked it would swell in the soldiers’ stomachs and kill them. Washington’s soldiers had to be restrained by the Oneidas until the corn could be properly prepared.

An Oneida woman named Polly Cooper also made the arduous trek to Valley Forge. It was she who taught the soldiers how to prepare the corn. The corn the Oneidas brought was white corn, which differs from the yellow corn most people eat. The white corn requires a different type of preparation and must be cooked for a longer period.

When the other Oneidas returned to their homes, Polly Cooper stayed with the troops to help care for them. After the war, the Colonial Army attempted to pay her for her valiant service, but she refused any recompense, saying it was her duty to aid friends when needed. She did accept a shawl and bonnet, however, as a token of appreciation from Martha Washington. The shawl has been handed down through the generations to Polly Cooper’s descendants.

Polly Cooper’s efforts were not isolated. Many Oneidas selflessly pledged their loyalty to the colonists throughout the war. In a poignant address in 1778, the Oneida sachem Ojistalak declared his nation’s “unalterable resolution … to hold fast the Covenant Chain of friendship and with you be buried in the same grave or share the fruits of victory and peace.”

But as peace dawned for the colonists, it was eclipsed for the Oneidas. Their decision to split with the other members of the confederacy led to ill feelings. Their once tranquil village of Oriska was destroyed, and its crops burned to the ground. In 1780, the Oneida fortress at present day Oneida Castle also was destroyed. The Oneidas were forced to flee their homes and find shelter and food in the Mohawk Valley. Despite all the privations the Oneidas withstood, Oneida warriors continued to support the colonists.

The American government in 1781 acknowledged the hardships endured by the Oneidas and offered gratitude for the Oneidas’ contribution to the war. Oneida delegates were told in a formal address presented by the Committee of Congress and Board of War: “At this period which we have the strongest reason to believe is not far distant, those will partake most in our confidence and regards who have been the most constant in their friendship towards us. [T]he faithful Oneidas … will then experience the good consequences of their Attachment to us and yourselves and your Children, when they share in the blessings of our prosperity, will thank the great spirits for inspiring you with so much Wisdom, Virtue and fortitude, as you have evidenced by the temporary distress you have suffered in our cause.”

In spite of the Oneidas recognition by the government, it wasn’t until about 1784 that they were able to return to their homeland: what was left of it. Nearly everything had been destroyed and had to be rebuilt. But more sorrow was to follow despite promises made by the federal government to preserve and protect the rights of the Oneidas to their ancestral lands.

The one promise the Oneidas received from the federal government was through the Nov. 11, 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua, which was signed between the United States and some nations of Haudenosaunee Confederacy. One of the paramount issues addressed by the treaty was that the United States acknowledged the lands reserved to the Oneidas and others in the confederacy. Within the lines of this paramount treaty the United States and Oneida Indian Nation agree to their boundaries and commit never to interfere with each other’s land:

“The United States acknowledges the lands reserved to the Oneida…, in their respective treaties with the State of New York, and called their reservations, to be their property; and the United States will never claim the same, nor their Indian friends residing thereon and united with them, in the free use and enjoyment thereof: but the said reservations shall remain theirs …”

Unlike the Treaty of Canandaigua, the Veterans Treaty signed Dec. 2, 1794 in Oneida Castle was specific to the Oneidas. The document was an agreement to indemnify Oneidas and Tuscaroras for losses and services in the Revolutionary War. This treaty is remarkable because it is the only one in which the United States commemorates victory jointly achieved with an Indian ally. The first lines of the treaty read:

“Whereas, in the late war between Great Britain and the United States of America, a body of the Oneida and Tuscarora … Indians, adhered faithfully to the United States, and assisted them with their warriors; and in consequence of this adherence and assistance, the Oneidas and Tuscaroras, at an unfortunate period of the war, were driven from their homes, and their houses were burnt and their property destroyed: And as the United States in the time of their distress, acknowledged their obligations to these faithful friends and promised to reward them: and the United States now being in a condition to fulfill the promises then made: the following articles are stipulated by the respective parties for that purpose…”

In January 1795, the Veterans Treaty was ratified by Congress. As a result the Oneidas received a cash settlement and sawmill. But the remainder of what was owed to the Oneidas — a church and gristmill – may never have been received as the Oneidas were still seeking both in 1805.

The promises from the federal government to the Oneida people were virtually ignored. New York State was hungry for Oneida land and through a series of unscrupulous “treaties” orchestrated by the state after the Revolutionary War, the Oneidas lost nearly all of their six-million-acre ancestral territory.

An Oneida leader, Good Peter, in a heartrending address, referring to attempts to claim Oneida land said:

“The voice of the birds from every quarter cried out ‘You have lost your country – You have lost your country – You have lost your country! You have acted unwisely and done wrong.’ And what increased the alarm was that the birds who made this cry were white birds.”

The Oneida Indian Nation has never doubted the principals that propelled it to enter the fight on the side of the colonists. The Nation adhered to its precepts of honor throughout the war and after, standing by its American allies. Oneida warriors from Oriska and beyond had heard the colonists call for independence and heralded its triumph.

The Oneida Indian Nation continues to honor the memory of all those who fought in the war and each year is a proud participant in the Battle of Oriskany commemoration ceremonies. (Editor’s note: This story was originally written for a publication by the Northern Frontier Project.)