By Kandice Watson, Documentarian

There are many stones and boulders scattered throughout Oneida and Madison counties related to the Oneida Indian Nation, and as the People of the Standing Stone, we are forever tied to these monoliths. Many people are aware of two prominent stones: The stone located at Nichols Pond named by Henry Schoolcraft to be our sacred stone and the Oneida Stone currently located outside of the Council House on Territory Road that used to sit in the Forest Hills Cemetery in Utica, NY. There are other stones in New York State that were used by the Haudenosaunee as trail markers or territorial boundary indicators, and some Nation Members place stones in their yards or near their homes as a way of tying themselves to our history and the land. The Skenandoah Boulder should also be included in this list of prominent stones as it is an important marker distinguishing a man who was instrumental in the perseverance of our people.

There were many Oneidas who performed valiantly during the Revolutionary War, but none gave as much as John Skenandoah (also Shenendoah). Skenandoah was born in Susquehannock Country in Pennsylvania at Conestoga and was later adopted into the Oneida Indian Nation’s Wolf Clan. He was an exceptional orator and often gave eloquent speeches to the people. He eventually became a Chief, although he did not hold a hereditary title. He is purported to have lived to be 110 years old and entertained guests in his home in Oneida Castle up until the time of his death. He was a Christian, having been converted by Samuel Kirkland in 1767, and always held great respect for his clergyman. In fact, it was his wish to be buried next to Samuel Kirkland in Clinton, NY after his death, which his Nation and family honored in 1816.

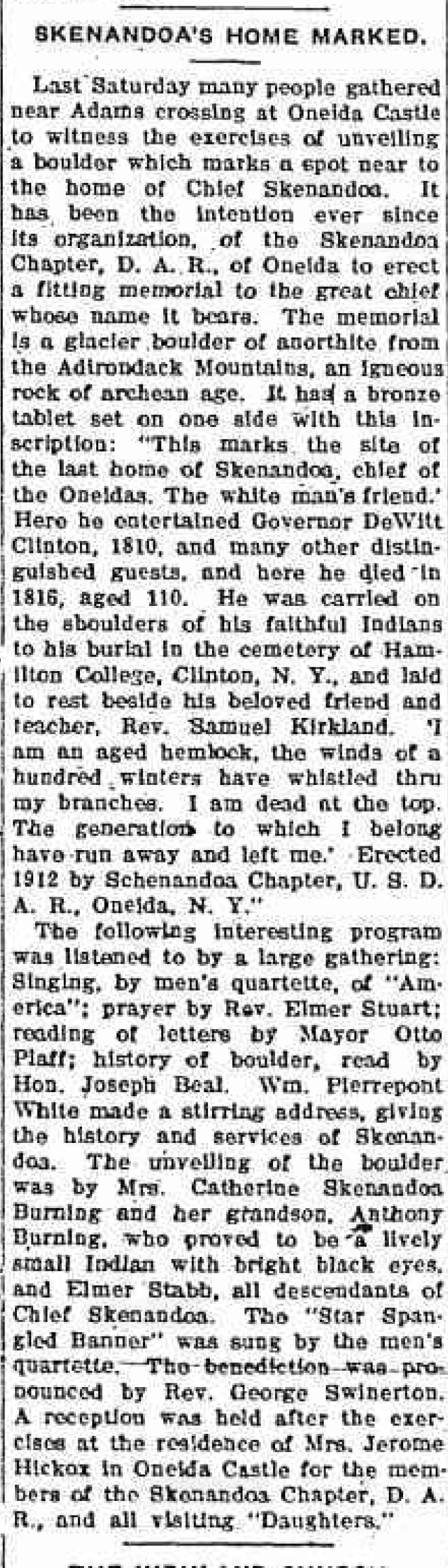

Skenandoah was given land in Kanonwalohale after the War, partly due to his military service in fighting on the side of the colonists, but also as a member of the Nation. His land was located near Route 5, Genesee St (called the Ambassador’s Trail at the time) and he was said to have built a large, red wood-framed house on the property in 1785 that survived the war. On September 21, 1912, the local Skenandoah Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution had a marker placed on the spot where his home was located in the 1800’s.

Clinton Courier, Sept. 15, 2012

It was a tremendous day, full with pomp and circumstance as the 7-ton syenite erratic boulder was placed on the site. Syenite is a coarse-grained intrusive igneous rock with a general composition similar to that of granite, but deficient in quartz, which, if present at all, occurs in relatively small concentrations. An erratic is a rock or boulder that differs from the surrounding rock and is believed to have been brought from a distance by glacial action. It is unknown where the syenite erratic boulder used for Skenandoah’s marker was brought from exactly. Similar stones in the area were retrieved from the Peekskill area, so this boulder may have originated from that area as well, after having been deposited there by earlier glaciers.

An engraved bronze tablet on the stone was unveiled by descendants of Skenandoah – Catherine Burning, Anthony Burning and Elmer Stabb – which read:

“This marks the site of the last home of Skenandoah, chief of the Oneidas. “The white man’s friend”. Here he entertained Governor Dewitt Clinton 1810, and many other distinguished guests, and here he died in 1816, aged 110. He was carried on the shoulders of his faithful Indians to his burial in the cemetery of Hamilton College, Clinton N.Y. and laid to rest beside his beloved friend and teacher, Rev. Samuel Kirkland.”

“I am an aged hemlock; the winds of an hundred winters have whistled through my branches. I am dead at the top. The generation to which I belonged have run away and left me.” – Skenandoah

Skenandoah was buried next to Samuel Kirkland (who died in 1808) upon his death in 1816, as he desired to be, but not initially in the Hamilton College cemetery as stated here. They were both buried on Kirkland’s property (today’s Harding Farm) and were later reinterred in the Hamilton College Cemetery in 1856, along with Kirkland’s daughter Eliza.

Hamilton College replaced Skenandoah’s grave marker in October 1999 when it became worn and very hard to read. The replacement was a nice version with a bronze plate. The old stone was then donated to the Oneida Indian Nation and placed in front of the Shako:wi Cultural Center, where it is displayed prominently.

The Skenandoah Boulder is an important icon within our Nation and deserves to be remembered just as all of our other stones of great worth. Oftentimes we forget the contributions of our Members, and having this boulder serve as a reminder to our people of our valued contributions to society and is vital to our collective memory.